Consumers are constantly influenced by subconscious factors.

From images, words, sounds, smells, tastes and even how things feel, there is a myriad of stimuli which can influence how consumers make decisions.

When these ‘hidden’ stimuli elicit an associated response, priming is at play.

What is priming?

Priming is a psychological technique whereby exposure to a certain stimulus may influence the response to a subsequent stimulus. That is, the first stimulus affects a person’s response to the second – it ‘primes’ them.

For example, when someone is exposed to the word ‘yellow’, they will then be faster to recognise the word ‘banana’ than if presented an unrelated word (like apple). Because yellow and banana are more closely associated in memory, people respond faster when the second word is presented.

Priming has been extensively studied in cognitive psychology for its pervasive influence on everyday human behaviour. It has also been extensively used across marketing and loyalty programs to influence brand perception and member engagement. In addition to priming, there are a number of other applicable behavioural biases in loyalty psychology which have been used to great success.

The evidence for priming

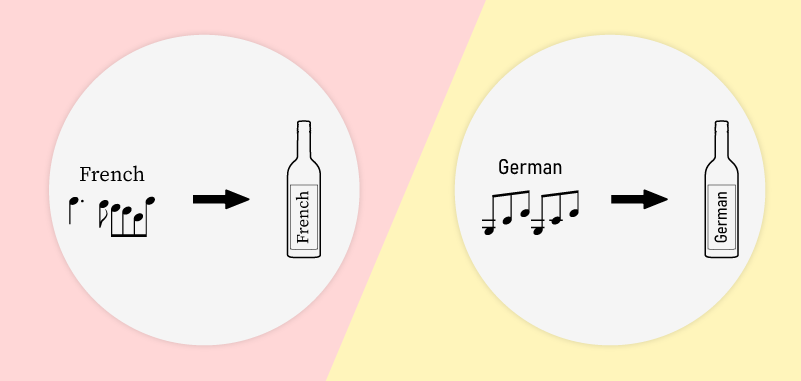

North et al (1999)[1] investigated the extent to which stereotypically French and German music could influence supermarket customers selecting of French and German wines.

Over a two-week period, French and German music was played on alternate days from an in-store display of French and German wines. French music led to French wines outselling German wines, whereas German music led to German wines outselling French wines. Responses to a questionnaire suggested that customers were unaware of these effects of music on their product choices.

Priming can have different effects on different people.

A study by Rick et al (2008)[2] tested the effect of priming on subjects who experienced different levels of anticipatory mental pain when paying for products (‘Spendthrifts’, who experience low pain vs ‘Tightwads’, who experience high pain). When primed with sad music, the Spendthrifts indicated they would spend more, while the Tightwads indicated they would spend less. Both strategies aimed to make them feel better: Spendthrifts cheered themselves up by going shopping, while Tightwads made themselves feel more in control by managing their budget. This provides some evidence for the need for segmentation strategies when utilising these types of approaches.

Another study by Brečić et al (2021)[3] looked at how in-store priming through textual and pictorial-based point of sale (POS) materials would influence the purchase of local foods in a supermarket setting. Through analysis of loyalty card transaction data, the research team determined priming local foods positively affected sales among those predisposed to them. Priming was most effective at the point of purchase as it reduced mental load and thus aided decision-making. This fieldwork provides evidence for the need for relevant marketing communications, which may be particularly effective when a consumer is at the peak of decision making.

Research has yet to firmly determine the duration of priming effects, but their onset can be almost instant.

Priming for loyalty

Promotions: For loyalty programs, understanding whether members respond better to bonus earn promotions, bonus redemption promotions or discount offers will increase the effectiveness of priming members to take a desired action. For example, informing the member they will earn bonus points for a transaction may act to reduce the mental pain of the member spending money. Point values

Labels and colours: Another application of priming is the use of status tier labels invoking value (e.g., Gold, Platinum, Emerald and Diamond). Drèze and Nunes (2009)[3] found that using status-laden colours (Gold and Silver) primed members to form a perception of a pyramid-shaped hierarchy without them needing to specify the percentage of customers in each tier. This was not the case when the colours Blue and Yellow were used. Colours and emotionally suggestive words or cues can strongly influence behaviour.

Membership status: Research shows highlighting a customers’ membership status results in a greater sense of belonging and customer satisfaction for members versus non-members.[4] Simply labelling customers as a ‘member’ can positively influence a customer’s evaluations of the brand and their loyalty program.

Anchoring: anchoring is a specific form of priming whereby the initial exposure to a number can serve as a reference point which influences subsequent judgement.[5] For example, a subscription program can provide multiple price points with one recommended option. Another example could be that a loyalty program member is provided a surprise loyalty bonus offer at checkout reducing the cost they expected to pay.

Suggestions: loyalty program operators can also tap into priming by providing customers with suggestions and targeted options which help the decision-making process. Supermarkets do this particularly well in how they position products not only in-store, but also digitally. By strategically placing suggested products alongside commonly purchased products within personalised communications (via an email or app), members become familiar with new products and are more likely to consider them for purchase.

Conclusion

People experience priming across fragmented sources every day; conversations, advertisements, reading product reviews, a seamless online checkout experience or a friendly wave at the local store.

Priming is a useful tool which can be used to influence consumer decisions in any industry. By making subtle (and ethical) trials and changes, loyalty program operators can realise the benefits.

It is often the subtlest things which influence the most.

[1] North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J. & McKendrick, J., 1999, ‘The influence of in-store music on wine selections.’ Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol 84, Iss 2, pp271-276.

[2] Rick, S. I., Cryder, C. E. & Loewenstein, G., 2008, ‘Tightwads and spendthrifts’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol 34, Iss 6, pp767–782.

[3] Brečić, R., Ćorić, D.S., Lučić, A., Gorton, M., Filipović, J., 2021, ‘Local food sales and point of sale priming: evidence from a supermarket field experiment’, European Journal of Marketing Vol. 55 No. 13, 2021 pp41-62.

[4] Drèze, X. & Nunes, J., 2009, ‘Feeling Superior: The Impact of Loyalty Program Structure on Consumers’ Perceptions of Status’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol 35, pp890-905.

[5] Söderlund, M., 2019, ‘Can the label ‘member’ in a loyalty program context boost customer satisfaction?’, The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2019, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp340–357.

[6] Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D., 1974, ‘Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases’, Science, Vol 185, Iss 4157, pp1124–1131.