“I’ve been running every day, but I haven’t had this many snacks in years” is what the creator of the hit sci-fi show ‘Black Mirror’ said in a recent interview about the impact of lockdown on daily life.

Whether it’s exercising to keep the snacks off or self-rewarding with a glass of wine for a good day of at-home productivity, people have had to change their daily behaviour and thus the self-motivation behind it.

This constant balancing act of right and wrong influencing everyday decisions is well studied by social psychologists, and it’s called ‘moral self-licensing’.

What is moral licensing?

Moral self-licensing, also known as ‘moral licensing’, ‘self-licensing’, or ‘licensing effect’, is a term used to describe the subconscious phenomenon whereby past good deeds ‘liberate individuals to engage in behaviours that are immoral, unethical, or otherwise problematic, behaviours that they would otherwise avoid for fear of feeling or appearing immoral’ (Merritt et al, 2010)[1].

Psychologically, consumers believe they can balance out their less favourable actions because of the good they have done in the past; an internalised bargaining system of good and bad decisions.

This is why people will tell themselves it’s okay to eat a couple extra slices of pizza because they went to the gym earlier that day, or their recent frugality licenses them to splurge on a new piece of designer clothing.

Psychological bargaining in people’s everyday behaviour is pervasive.

When Good Frees Us to Be Bad

Research suggests that moral self-licensing effect on individual behaviour is present in a variety of contexts; for example, one study showed people who expressed support for president Obama were granted ‘moral credentials’ for their actions, and thus were likely to be racist or prejudiced afterwards (Effron et al 2009)[2] Another study demonstrated the influence of moral self-licensing in health-related decision making; people who adhere to diets or participate in regular fitness-related activities allow themselves moments of indulgence because they have ‘earned’ it.[3]

In terms of consumer purchasing behaviour, participants of one study were twice as likely to purchase a luxury item when asked to commit a charitable act prior to shopping.[4] Most notably, the study revealed people do not have to do good for the effect to happen, rather, the mere mention of a chance to do good is enough to boost the self-image. The same effect can be obtained vicariously when a person observes another person from a group they identify with make an altruistic decision.[5] Two interesting applications for brands to consider.

A study on the self-licensing effect in loyalty programs revealed the higher level of effort required to obtain different rewards tended to shift member preferences from necessity to luxury rewards; with the effect being stronger on members who are more inclined to feel guilty about luxury consumption.[6]

The Presence of Self-Licensing in Brands and Customer Loyalty

Loyalty programs give members the chance to indulge in luxuries they would not have given themselves license to buy with their own money.

For example, many frequent flyer program members refuse to pay for business class seats but have no problem redeeming points for upgrades – this is in fact the most popular way for members to spend points.

Any brand that provides some form of social-giving aspect alongside their product or service is also tapping into self-licensing, intentionally or not.

TOMS

One for one, or buy-one give-one, is the social business model credited to TOMS Shoes; for every pair of shoes a customer buys, the company donates a pair to someone in need. The promise of the brand to do something good or altruistic on the customers behalf may cause them to feel more self-licensed, and thus increase the likelihood of purchase.

DSW VIP

An example of a loyalty program with charitable giving is DSW VIP from Designer Shoe Warehouse, an online footwear retailer. The program hits social philanthropy on both the points earn and burn side: members are rewarded with points when they donate new or gently worn shoes, and members have the annual option to donate 2.5% of what they spend to charity.

Humble Choice

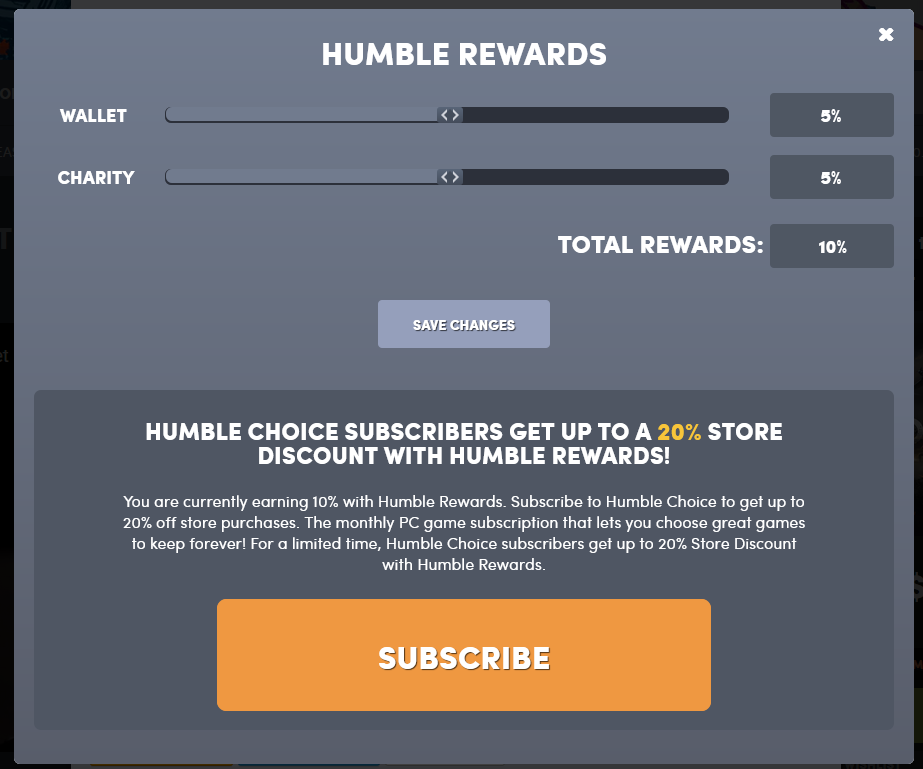

Similarly, Humble Bundle is a digital storefront for video games where a portion of the price goes towards charity. The storefront has evolved to include a subscription model, Humble Choice, where members choose games every month and receive a further 10-20% discount off individual purchases. For each purchase, members have the unique option to claim how much of this discount they want for themselves or how much they want to go to charity.

The two examples of DSW and Humble Bundle reiterate the earlier point of moral self-licensing influencing consumer behaviour. Having the option to give back increases engagement by providing genuine purpose to the customer decision.

Even if they do not act on it, research has shown the effect is still elicited and customers will feel good about themselves. This might be enough to boost not only the self-image, but also the image and loyalty to a brand.

Closing thoughts

When programs offer highly desirable, unique, and pleasure-providing rewards which members would not normally purchase, moral self-licensing can be drawn out. Providing members with the opportunity to perform licensing acts like purposeful or charitable deeds during the reward process can further amplify the effect.

Learning why people feel licensed to engage in particular behaviours allows for a better understanding of why people act the way they do; and this is as important for businesses to understand about their customers as it is for the individual self.

To read more about consumer psychology and how it applies to loyalty programs have a read of these articles on the endowment effect or surprise and delight.

Interested in exploring the latest trends and insights in consumer psychology and loyalty? Let’s chat! Get in touch to discuss how we can help you stay ahead of the game.

[1] Merritt, A.C., Effron, D.A. and Monin, B. (2010), Moral Self‐Licensing: When Being Good Frees Us to Be Bad. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4: 344-357.

[2] Effron, Daniel & Cameron, Jessica & Monin, Benoît. (2009). Endorsing Obama Licenses Favoring Whites. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 45. 590-593.

[3] Isherwood, J.C. (2015), Licensing in the Eating Domain: Implications for Effective Self-Control Maintenance. Dissertation, Duke University.

[4] Khan, U. & Dhar, R. (2006, “Licensing effect in consumer choice”, Journal of Marketing Research. 43(2): 259–266.

[5]Kouchaki, M. (2011). “Vicarious moral licensing: The influence of others’ past moral actions on moral behavior”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 101 (4): 702–715.

[6] Kivetz, Ran & Simonson, Itamar. (2002). Earning the Right to Indulge: Effort as a Determinant of Customer Preferences Toward Frequency Program Rewards. Journal of Marketing Research – J MARKET RES-CHICAGO. 39. 155-170. 10.1509/jmkr.39.2.155.19084.