Loyalty programs have been around for hundreds of years, with approaches becoming more sophisticated over time. This article chronologically details the evolution of currency-based loyalty programs with extensive evidence to support the research.

Beer and Bread Tokens (Ancient Egypt)

In Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation,[1] Professor Barry Kemp argues that ancient Egyptians practised a type of incentivisation program similar to modern frequent flyer programs, including the presence of status tiers and the ability to redeem tokens.

For much of the pharaohs’ thousands of years of rule, they did not have money. It simply was not invented yet. Instead, citizens, conscripted workers and slaves alike were all awarded commodity ‘tokens’ (similar to loyalty points or miles) for their work and temple time. The most common were beer and bread tokens. The tokens were physical things, made from wood, then plastered over and painted and shaped like a jug of beer or a loaf of bread.

The more senior people in the hierarchy were rewarded with the same tokens but received multiplier bonuses. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus details examples and mathematical equations regarding how higher positions, such as the skipper, crew leader and doorkeeper, received double bread tokens compared to the rest of the crew. This could be construed as a variant of the status tier bonus, where higher tier members earn bonus points for transactions to reward them for their greater loyalty.

The tokens could also be exchanged for things other than bread and beer. Those high up enough to earn surplus tokens could redeem them on other goods and services, in the same way that frequent flyer members with lots of points can redeem them on flights and on non-flight rewards such as iPads, KitchenAid mixers, and Gucci handbags.

While some of the characteristics are quite similar, was this really a loyalty program? Some might argue it is simply a societal exchange system developed in the absence of fiat currency. Others might contend that is exactly what a modern loyalty program design is: a non-fiat exchange system utilising tokenised currencies.

Copper Tokens (c. 1700 – 1800s)

The first modern loyalty program, according to a New York Times article by Nagle (1973),[2] commenced in 1793, when a Sudbury, New Hampshire merchant began rewarding customers with ‘copper tokens’. The tokens could be accumulated and used for future purchases, thereby generating repeat visits, the core behavioural objective of loyalty program design. The idea was quickly replicated by other retailers and carried into the 19th century.

Is there evidence to support this claim? While copper loyalty tokens from Sudbury dating back to 1793 could not be found, Loyalty & Reward Co research did identify other merchant-branded copper, brass and aluminium tokens created in the US in the 1800s. For example, the New York Times article by Nagle refers to a brass token created by Robinson and Ballou Grocers, dated 1863, which can be found online for sale by various coin dealers worldwide for as little as US$50.

This would appear to provide support for the existence of merchant loyalty tokens, however further investigation reveals these coins to be more accurately referred to as ‘Civil War’ tokens, which were not related to loyalty programs at all.

During the 1861-64 US Civil War, high inflation sparked a frenzy of hoarding, with the focus on gold, silver and copper coins. With few coins left in circulation, merchants began to suffer as small denomination coins were the most commonly tendered at that point in time. To alleviate the situation, merchants began minting their own tokens to fill the void.[3] These were typically one cent in value, made of copper or brass, and were similar in size to government-issued coinage.

This was not the first time such an approach has been taken by merchants. Between 1832-1844, ‘Hard Times’ tokens were created when the United States went through an economic depression over the fate of the Second Bank of the United States and the powers of the Federal Treasury.

The climax of that period was the ‘Panic of 1837’, brought on by President Andrew Jackson’s requirement that banks and receivers of public money only accept gold or silver in payment for public lands as a way to reduce speculation. As a result, gold and silver were hoarded and loans were called in, generating a run on the banks. An insight from an article by the American Numismatic Association (Mudd, 2015)[4] states, ‘The immediate reason for the issuance of the tokens was the ongoing shortage of small change in the United States – a situation that had existed ever since the Colonial period despite the best efforts of the United States Mint’.

This provides an important clue for the investigation of the famed Sudbury merchant from 1793. It appears that coinage shortages also existed at that time right across the United States. A Quarterly Journal of Economics article (Barnard, 1917)[5] references merchants minting their own coins of brass and tin as early as 1701 after the Massachusetts mint was closed in 1697. Further examples are cited from Virginia as early as 1714, with many more coins created between 1773-74. In Connecticut, copper mine owner John Higley created the first recorded copper tokens between 1737-39, while Chalmers, a goldsmith of Annapolis, Maryland issued tokens in at least three denominations (shillings, sixpence, and threepence) just after the American Revolution in 1783. Barnard states that so many other merchants created silver and copper coins that laws were passed by Pennsylvania, Connecticut and New Jersey prohibiting the circulation of coins not expressly authorised.

Thus, the historical record appears to show the primary driving force for the creation by merchants of branded copper (and other metal) tokens was to address a severe shortage of coinage which was inhibiting commerce.

This phenomenon was not restricted to the US, either. There is significant evidence of local governments and merchants creating their own coinage during periods of shortages in the United Kingdom from as early as 1577.[6]

Did a Sudbury, New Hampshire merchant invent the world’s first loyalty program when they began rewarding customers with copper tokens in 1793? It is possible that such a merchant created branded copper tokens, however there is no evidence to support the claim made in the New York Times article (and repeated extensively across numerous books and websites) that they created the tokens in order to reward loyal customers. In fact, the likelihood is they were created to address a local coin shortage, and this was later misinterpreted as an early form of loyalty program currency.

Irrespective, the Coinage Act of 1864 enacted by Congress made the minting and usage of non-government-issued coins illegal, ending this era forever.

Co-op Dividends and Tokens (1812)

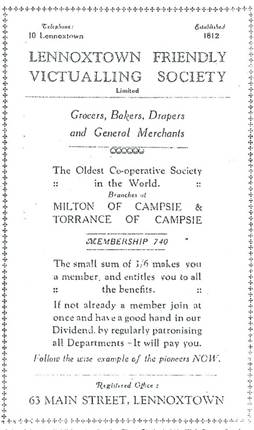

To provide local residents with access to essential goods at the lowest cost possible, co-operative societies began to emerge in the United Kingdom in the early 19th century. The Lennoxtown Friendly Victualling Society was established in Scotland in 1812, with later advertising claiming it was ‘The Oldest Co-operative in the World’.[7] By paying an annual fee, members were provided with a membership number, and the right to purchase goods from their stores. The society included a grocer, chemist, bakery, butcher, drapery, milk and coal deliveries, and even a shoe shop.[8] This new type of system, pioneered by mill workers, involved buying goods in bulk, selling them at a profit, and then sharing the profits out amongst members in the form of a dividend. Importantly, the dividend payment received was based on the amount they spent over the corresponding period.

Other co-operatives followed with similar models, including the Rochdale Pioneers in 1844.

Although not specifically stated, it is suspected that early Lennoxtown Friendly Victualling Society member transactions were recorded in a ledger which was later used to calculate the dividend.

Some co-operatives started to issue members with paper dividend vouchers when they transacted, and during specific periods of the year (typically annually, bi-annually or quarterly), they could redeem their vouchers for a cash payment of equivalent value.

In the mid-1850s, many co-operatives moved to issuing members with metal tokens which displayed their branding and the value of the amount spent by the member.[9]

On the day that members could claim their dividend (so-called ‘divvi days’), the paper or metal tokens would be presented and the cash payment made. Interestingly, the amount paid would vary from period to period, encouraging some members to hold their tokens in the hope of gaining a better dividend in the future. As with modern loyalty programs, the co-operative was required to maintain sufficient revenues to cover the liability associated with tokens in circulation, meaning retained tokens could lead to financial challenges.

The co-operative token program design was incredibly successful and spread around the globe, providing workers with access to better value goods and services.

From the author’s perspective, the co-operative token system should be considered the world’s first loyalty program; consumers proceeded through a formal registration process, tokens were issued and accumulated based on the amount spent as a defined-value loyalty currency, the value of the tokens would vary when redeemed, and the co-operative would follow proper accounting procedures to manage the associated liability. The program served to acquire members, stimulate spend (especially share of wallet consolidation), retain, drive advocacy, and even collect and use data.

B.T. Babbitt Inc. (1850s)

In the United States, a non-co-operative loyalty program model emerged invented by innovator and pioneer, B.T. Babbitt.

Born in 1809, Benjamin Talbot Babbitt found his fortune in New York City in the early 1830s by designing an original and cheaper process to make saleratus, a key base ingredient of baking powder. He soon expanded his product range to include yeast, baking powder and soap powder. He became the first to sell individually wrapped bars of soap, with ‘Babbitt’s Best Soap’ becoming a household name across the United States.[10]

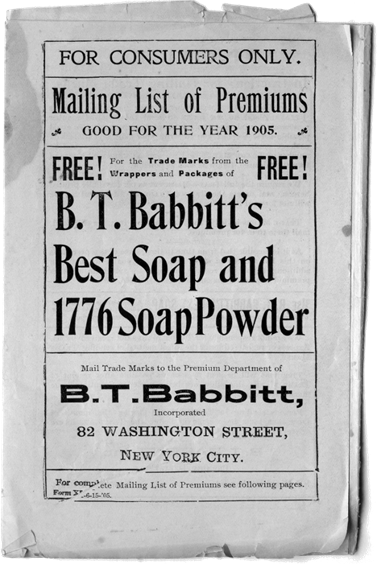

To boost repeat sales, in the 1850s[11] B.T. Babbitt, Inc. launched a new (and truly revolutionary) promotional program, where they invited customers to cut out and collect the ‘trade marks’ from product packaging of Best Soap and 1776 Soap Powder. The trade marks could initially be redeemed for coloured lithographs by mailing them to the company. Soon after, the rewards range was expanded into a more comprehensive offering, which was promoted in the company’s ‘Mailing List of Premiums’.

As an example of the rewards on offer, the 1905 Mailing List of Premiums offers a wide range of choices, including a harmonica, felt pencil case or box of school crayons for 25 trade marks; a buckhorn handle pocket knife (2 blades), sterling silver thimble or pair of Uncle Sam suspenders for 50 trade marks; all the way up to a lady’s locket chain (14k gold filled), lady’s gold ring (12 pearls), or lady’s handbag for 225 trade marks.[12] These are not just practical, utilitarian products, but truly aspirational items which would have captivated the member base in a way which history had never seen before.

B.T. Babbitt also introduced the option for customers to visit their premium stores located in major cities across the US, as well as Canada, Puerto Rico and Scotland, to redeem trade marks for ‘a large number of household articles, dolls, toys, etc.’.

As a new approach to marketing, the company positioned the program as a profit-sharing plan, potentially taking inspiration from dividends paid on shares, or rebates for volume sales. The 1912 B.T. Babbitt’s Profit Sharing List[13] states ‘B.T. Babbitt was the originator of premiums… the firm has continued since that time to give its customers in the form of premiums a very material share of the profits of its immense business.’.

The Profit Share Plan also cautions, ‘When you buy all B.T. Babbitt’s Products, consisting of Soaps, Cleanser, ‘1776’ Soap Powder, and Pure Lye or Potash, you are entitled to a return in the form of a premium. If you do not save the trade marks from any of the Babbitt articles you are losing just so much. These trade marks are worth fully one-half cent each to you if redeemed from our premiums.’

Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. (1860s)

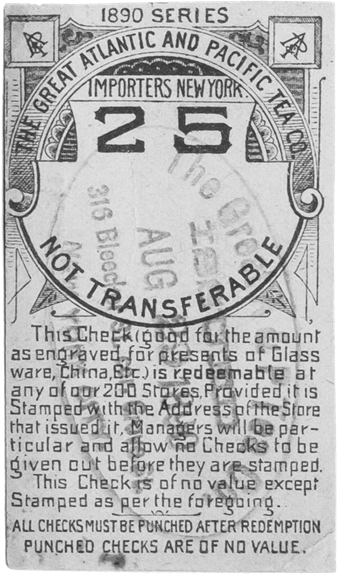

In the 1860s, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. (which was set to become the largest retailer in the world under the A&P brand between the 1920s and 1960s)[14] launched a comparable program to reward their customers for purchasing a selection of their products. When transacting, customers would receive a red coupon known as a ‘check’, detailing the amount it was worth and the terms. One 1890 example states, ‘This Check (good for the amount as engraved for presents of Glass ware, China, etc.) is redeemable at any of our 200 Stores. Provided it is Stamped with the Address of the Store that issued it. Managers will be particular and allow no Checks to be given out before they are stamped. This Check is of no value except Stamped as per the foregoing. ALL CHECKS MUST BE PUNCHED AFTER REDEMPTION. PUNCHED CHECKS ARE OF NO VALUE.’[15]

Checks could be accumulated and redeemed in stores for a range of consumer goods. This was incredibly popular with customers, and it provided a strategic competitive advantage over smaller merchants who could not afford, and did not have the space, to provide such a sizeable reward range.

It also posed some challenges. According to Levinson[16], ‘the premiums not only were costly, but also took up shelf space that could have displayed merchandise for sale. Many stores of the period looked more like gift shops than groceries.’

To address this issue, in the early 1900s the company published The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. Catalogue. This promoted a range of day-to-day homeware products including saucepans, teapots, knives, ironing boards, sugar tins, wash bowls, spoons, bread trays and more.[17] Once enough checks had been saved, members could send them to a central office and receive the reward by return freight,[18] reducing the need for each store to stock the full range.

A few years later, The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co transferred their loyalty program operations to Sperry & Hutchinson, a stamp program covered later in this chapter.

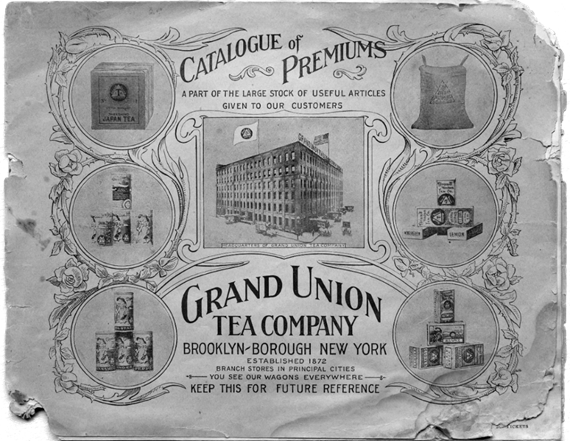

Grand Union Tea Company (1872)

The Grand Union Tea Company was formed in 1872 in Pennsylvania and followed the lead of the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co with their loyalty program design. The owners chose to sidestep retailers and sell their product directly to consumers, starting with door-to-door sales. They rewarded customers with ‘tickets’ which could be collected and redeemed for a wide selection of products from the company’s Catalogue of Premiums.[19] The 1903 version of the Catalogue of Premiums lists the full product range and prices (coffee, tea, spices, extracts, baking powder, soap, and sundries), as well as seventeen pages of rewards. These include an Oak Roman Chair (100 tickets), lace curtains (120 tickets a pair), Ormolu clock (300 tickets) and dinner set Berlin 1903 (440 tickets). Customers could earn one ticket by buying a pound of coffee at 20 cents, two tickets for premium tea at 40 cents and one ticket for a packet of cloves at 10 cents. The catalogue proudly proclaims, ‘We advertise by giving presents with our goods, thus SHARING WITH OUR CUSTOMERS the profits of our business. Remember, you pay less for our goods of same quality than at other stores, and get presents in addition.’

The 1971 New York Times article by Nagle included an interview with William H. Preis, senior vice president of the Grand Union Tea Company. Preis joined the company in 1933. By the time of the interview, the company had transitioned their tickets program to a coalition-based stamps program run by Stop & Save Trading Corporation. Customers could earn Triple-S Blue Stamps which cost the company 1 ¼ per cent of sales. Preis indicated they had been providing the stamps program for 16 years.[20]

Larkin Company (1875)

The Larkin Company launched the Larkin Plan in 1875, which encouraged women to form a ‘Club-Of-Ten’ or mini buying co-operative that purchased via mail order, thereby side-stepping retailers. This innovative approach was an early example of a loyalty program community strategy. It rewarded members with a 20 per cent return on spend in the form of certificates, which were later converted to coupons. Certificates and coupons could be used for future purchases from the Larkin Family-To-Factory Plan catalogue. Goods sold by Larkin Company included cleaning and laundry supplies, soap, shaving cream, cosmetics, hair care, perfumes and colognes, teas, coffee, spices, pasta and sauces, pharmaceutical products, toiletries, cutlery, hardware, paint, polishes, stationery and an extensive range of clothes.

The 1905 catalogue provides an extensive two-page overview of the ‘Club-Of-Ten’ program, then detailed 49 pages of rewards (referred to as ‘Premiums’). The authors’ copy includes a product order sheet that has been partially filled out, including ten boxes of Sweet Home family soap, seven boxes of White Woolen soap, fifteen packages of Boraxine soap powder, and one bottle of Larkin Essence of Jamaica Ginger. Throughout the catalogue, a large number of items have been circled in pencil with a note detailing what room they would reside in (parlour, kitchen, dining, laundry, etc).

The 1910 catalogue is a weighty 132-page Product and Premium List with over 400 categories of rewards. The cover declares The Larkin Co as the world’s largest manufacturers of soaps, perfumes and toilet preparations. Also included in the author’s copy of the catalogue is a six-page insert supplement added after the main catalogue was printed.

Details on the program extend to six pages and include a registration form to create a new ‘Club-Of-Ten’.

The twelve centre pages are full-colour and promote rugs, hammocks, clocks and lamps as exotic rewards.

The 1915 catalogue boasts ‘the co-operative buying power of over two million homes!’ with over one hundred thousand ‘Club-Of-Ten’ groups formed, providing insight into the success of the model.

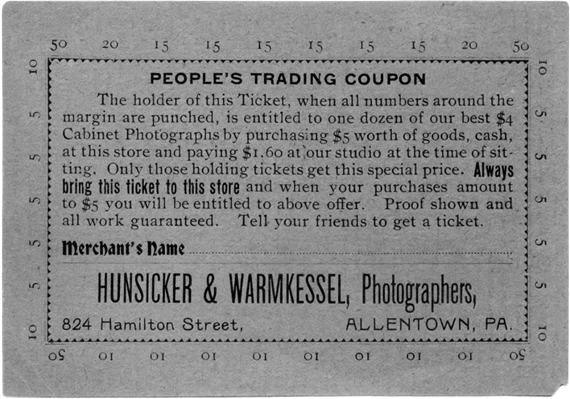

Hunsicker & Warmkessell Photographers (1890)

Although the original launch date of the program is unknown, an example from 1890 is a ‘People’s Trading Coupon’ from Hunsicker & Warmkessell Photographers, based in Allentown, Philadelphia. The coupon is a sophisticated punch card which, when completed, provides the member with ‘one dozen of our best $4 Cabinet Photographs’. The member is reminded to ‘Tell your friends to get a ticket.’[21]

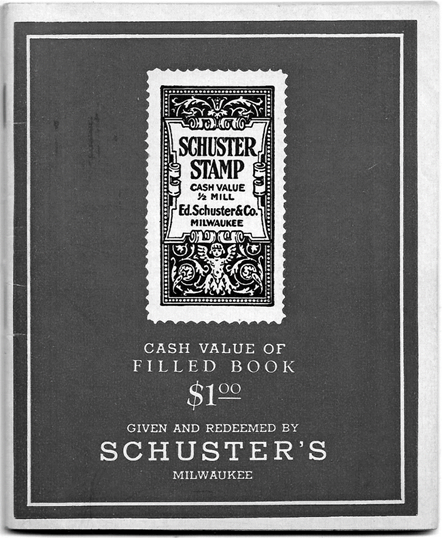

Schuster’s Department Store (1891)

In 1891, a new innovation was introduced that was set to dominate loyalty programs for the next eighty years. Schuster’s Department Store in Milwaukee began using physical ‘stamps’ to reward loyal customers. Customers could earn stamps when making purchases and were encouraged to stick them into collecting books. The books could then be exchanged for a wide range of rewards. Customers earned one stamp for every 10¢ spent. A filled book of 500 stamps was worth US$1 to redeem on rewards (a 2 per cent return on spend).

By the Second World War, it appears the program had expanded into a small coalition, with a stamp book dating from that era promoting ‘Valuable Schuster Stamps Are Now Also Given By Many Food Markets.’[22]

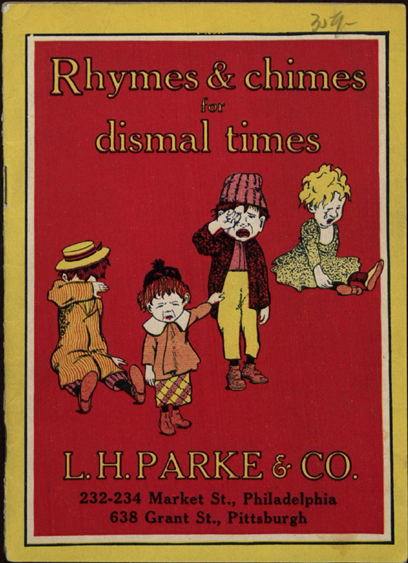

L.H. Parke and Company (1895)

L.H. Parke Company, a Philadelphia and Pittsburgh manufacturer and distributor of food products including coffee, tea, spices, and canned goods, established their trading stamp program in 1895. Customers were rewarded with Parke’s Blue Point Trading Stamps when purchasing Parke’s products in grocery stores across Pennsylvania and New Jersey. They were instructed to paste them in a book. Nine hundred and ninety stamps were required to complete a book, and multiple books could be redeemed for a wide range of household rewards referred to as Premiums (potentially borrowing from the Grand Union Tea Company program).

The program was so successful, Parke established showrooms in their headquarters buildings in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, inviting customers to browse premium goods and redeem their stamps on the spot. You are always welcome at our Art Rooms,’ a 1900 catalogue proclaims, ‘where you can inspect the Premiums’.[23] This potentially represents the first example of a dedicated redemption centre for a loyalty program (as distinct from the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co where the rewards were featured alongside grocery items).

In addition, the company identified the marketing cost savings associated with a loyalty program, even using it as a feature of promoting the program. ‘These valuable Premiums … are part of a plan to give the users of our goods the money we would ordinarily spend on advertising.’

This image is published with permission from Hagley Museum and Library.

The Sperry & Hutchinson Company (1896)

In 1896, The Sperry & Hutchinson Company took the stamps model and innovated further. They introduced what is understood to be the world’s first coalition loyalty program. Rather than a company issuing their own loyalty currency as a proprietary program, Sperry & Hutchinson created the entire loyalty program apparatus as a service.

New England retailers were provided with S&H Green Stamps, books, and catalogues to provide to their customers, and customers could redeem the books directly with Sperry & Hutchinson, thereby removing from retailers the logistical challenges associated with running a loyalty program.

Other companies quickly replicated their model (Gold Bond, Gift House, Top Value and King Korn amongst some of their competitors)[24], but Sperry & Hutchinson remained the biggest globally. At one point, they claimed they were distributing three times as many Green Stamps as the US Postal Service was distributing postal stamps.

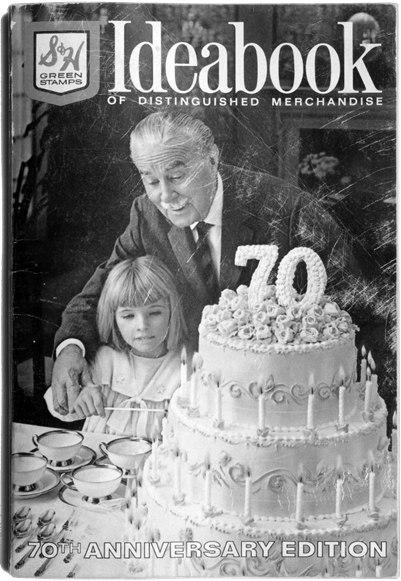

Every year, Sperry & Hutchinson would release a print version of their catalogue. The 1927 version was titled the S&H Green Stamps Premiums catalogue.

By 1966, it had evolved into the Ideabook of Distinguished Merchandise. This 70th Anniversary Edition[25] provides insight into the scale and complexity of S&H operations when at the height of their popularity. In addition to being able to order rewards via post, members could visit a vast network of redemption centres, with the entire product range priced in books of stamps. The 185-page catalogue contains over 2,000 products across 59 categories, a similar sized range to some modern frequent flyer program online stores. In the copy possessed by the authors, a young female (assumed) has worked her way through the girls’ toys’ pages, circling the items she desired and writing out the number of books she needed to claim everything on her list. It provides a sense of the process so many households around the world would have followed in deciding which rewards they wanted to aim for, with much discussion and debate ensuing.

The (pre-computer and internet) logistics for claiming stamp rewards were extensive; the member needed to fill books with stamps, choose the reward products, fill out a separate order form for each reward, then send the books and order forms (plus applicable sales taxes) via first-class mail to their nearest distribution centre. Alternatively, the member could visit one of hundreds of retail outlets and spend the stamp books directly. The overheads of running such a massive operation would have been enormous.

The demand for stamps went through several phases during the 1900s. According to the US National Commission on Food Marketing,[26] by 1914 around 7 per cent of retail trade involved the awarding of stamps. This reduced to 2 per cent during the First World War. The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co dropped S&H Green Stamps altogether during the war, which would have been a major blow to Sperry & Hutchinson, as they lost the largest grocery chain in the country. Stamp earning stabilised at 2 to 3 per cent of retail trade during the 1920s but fell substantially during the Great Depression and all the way through the Second World War.

Post-war, interest in stamps increased substantially. Thirty million US dollars’ worth of industry stamp sales were recorded in 1950 in the US, and this grew to US$754 million by 1963, accounting for 16 per cent of total retail trade, and a whopping 47 per cent of grocery trade. Research from the period by Benson and Benson Consumer Studies indicated 83 per cent of all families in the US were saving stamps.[27]

In the US alone, there were an estimated 250 to 500 stamp companies operating at the peak of ‘the golden age of stamps’.[28]

Stamps also appear to have been the catalyst for expansion of loyalty programs globally. In the UK, Green Shield and Co-Op Stamps were two popular programs, while in Australia, Green Coupon, Aussie Blue and Group Tokens operated in a competitive market. Other countries also adopted stamps en masse, including Sweden, Poland, Switzerland, Canada, Austria, Germany and many more.

Of notable interest is two case studies documented by the US National Commission on Food Marketing which measured whether stamps were successful in helping companies grow revenue.[29] The first related to a business which introduced stamps in a market which did not previously have stamps. The second related to a business which introduced stamps in a market where stamps were already used extensively by their main competitors. While the circumstances for the two studies were different, in both instances within two years gross margins increased by an amount exceeding the cost of the stamps, demonstrating the programs were a success in generating incremental profits.

This is potentially one of the earliest examples of research conducted demonstrating loyalty programs can be effective in generating member spend and retention.

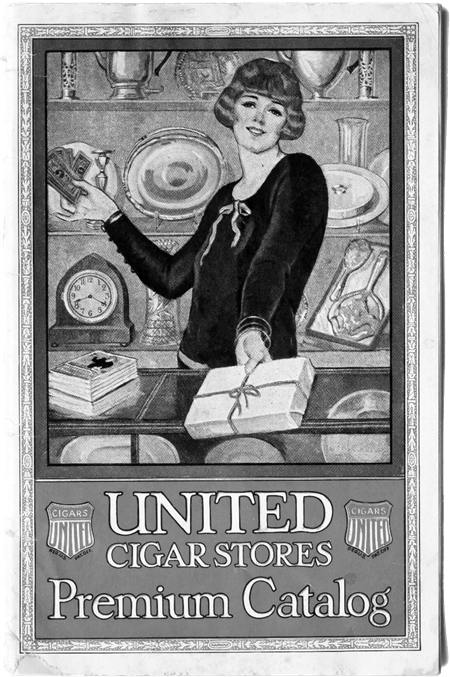

United Cigars Store Co (1901)

Another example is The United Cigars Store Co., founded in 1901 and sporting over 3,000 retail outlets at its peak in 1926.[30] They ran a successful ‘certificates and coupons’ rewards program (where five coupons were equal to one certificate). United built a coalition of partners by making deals with companies including Wrigley’s, Swift’s, Danish Pride, National, Barkers, Votan and Tootsie, all of which put United coupons within their product packaging. Certificates and coupons were redeemable by mail or at 250 redemption centres around the country. Rewards included a men’s gold-filled watch or six place settings of Rogers silver plate flatware (900 coupons), room-size oriental-style rug (4,000 coupons), a Remington automatic shotgun (5,000 coupons), and a four-wheel Studebaker carriage (25,000 coupons).

The United Cigars Store Co 1924 Premium Catalog[31] features a selection of well over one thousand reward items, including clothing, umbrellas, smoking accessories, razors, cutlery, leather goods, toiletries, jewellery, clocks, watches, kitchenware, headphones, cameras, sporting goods, toys, games and silverware.

Betty Crocker (1921)

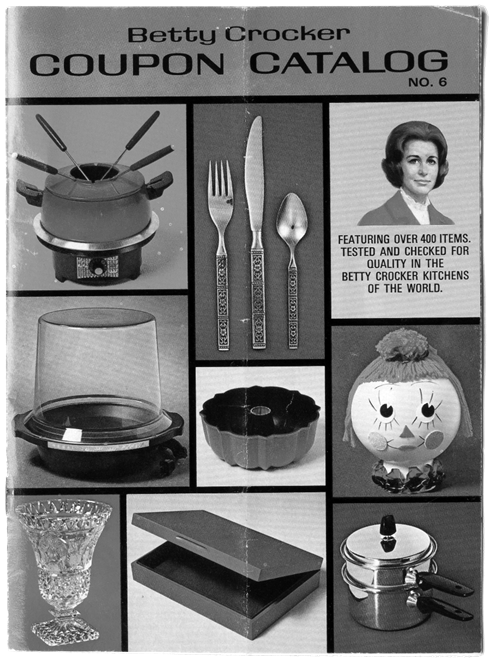

Stamps were not the only major loyalty currency during this period. In 1921, The Washburn Crosby Company, a flour-milling company and largest predecessor of General Mills, Inc., invented fictional character Betty Crocker to personalise responses to consumer enquiries generated by a promotion for Gold Medal flour.[32] In 1931, the company included a coupon for a silver-plated spoon within Wheaties cereal boxes and bags of Gold Medal flour.[33] The promotion was so successful, the company followed up the next year with a coupon program which allowed customers to access a complete set of flatware. Starting from 1937, the ‘Betty Crocker Coupons’ were printed on the outside of the box, enabling customers to see how many they could earn with the purchase. In 1962, the Betty Crocker Coupon Catalog was released, an annual publication ‘Featuring over 400 items tested and checked for quality in the Betty Crocker kitchens of the world’.[34]

A study of the history of Betty Crocker Coupons introduces the concept of emotional engagement generated by a loyalty program. Mark Bergen, marketing department chair at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management, said the Betty Crocker program was remarkable for two characteristics – its longevity and the depth of emotion it inspired among its devotees. It became more than a coupon redemption program, Bergen said, by working its way into the fabric of family life.[35]

The mid-1960s marked the beginning of the slow demise of stamps. Some supermarkets dropped stamps and found success by focusing their brand positioning on lowest prices to differentiate against competitors. This approach soon spread to other retail and discount stores.

In the 1970s, a series of recessions and the world oil shock created hardship for most stamp coalition operators, as retail partners sought any way to cut costs. Large-scale rejection of stamps by retailers led to a sudden drop in revenue, and combined with the large cost overheads, ongoing operations became incredibly challenging.

To understand the size of such savings made by supermarkets, in 1977 Tesco in the UK ditched Green Shield Stamps, saving the company an estimated £20 million a year[36] (the equivalent of £120 million today), which they reinvested in cutting costs.

Texas International Airlines (1979)

Texas International Airlines (TIA) pioneered the world’s first modern frequent-flyer program in 1979.[1] Dubbed the ‘Payola Pass’, the program was launched in response to increasing competition as a result of the deregulation of the US airline industry in 1978.[2] Under deregulation, routes and fares were no longer fixed by authorities, forcing airlines to compete directly on price and service.

The design of the Payola Pass program was straightforward yet groundbreaking. Passengers were awarded coupons for each flight segment they flew on, with one mile flown equal to one mile earned. Once a traveller accumulated a predetermined number of miles coupons, they could redeem them for a free ticket. This operational model mirrored the logic of earlier retail stamp programs, but its execution in air travel was novel. Texas International leveraged its reservations system to track each customer’s accrued mileage, an innovative move that automated the tally of miles flow and removed the need for paper stamp booklets.

As a pioneering effort by a small airline, the Payola Pass program proved short-lived. In October 1982, Texas International was merged into Continental Airlines, effectively bringing the Payola Pass program to an end.

American Airlines (1981)

Potentially inspired by Payola Pass, in 1981, American Airlines launched AAdvantage which rewarded members with digital miles (rather than paper coupons) corresponding to how many miles a member had flown.[3] AAdvantage was soon followed by similar schemes from United Airlines, TWA and Delta Airlines.[4]

In 1982, American Airlines upped the ante by introducing a Gold tier to recognise their most loyal members. The same year they launched earn partnerships with Hertz, Holland America Line and British Airways, forming the basis of the first modern coalition program.

Over the next five years, a boom in miles and points-based loyalty programs ensued, including new programs from Holiday Inn (the first hotel program), Japan Airlines, Marriott, Alaska Airlines, Aeroplan, Korean Air, Pan Am, Northwest Airlines, Continental Airlines (which, in conjunction with the Bank of Main Midland, launched the world’s first co-branded credit card program), Hilton, Hyatt, National Car Rental, Southwest Airlines (which introduced ‘points’ rather than ‘miles’ for the first time), Qantas, and Diners Club.

As happened with American Airlines, soon after the launch of these large programs, hotel and car rental companies began partnering with the airlines and started offering miles and points as a strategy to grow their share of the lucrative business traveller and high-value leisure traveller markets.

With the rapid expansion of the frequent flyer and hotel coalition models and their new currencies, banks and retailers soon replicated their approach. Points and miles loyalty programs quickly became the dominant loyalty program currency globally, ending the ninety-year reign of stamps.

General Mills tried to revitalise the Betty Crocker program by changing coupons to points in 1989.[39] The program was eventually retired in 2006, with Bergen of the Carlson School arguing the decline in engagement was due to shopping pattern changes.[40] Households had given up the habit of saving for a future purchase and started buying on credit, while the idea of cutting out box-top coupons and sending them in the mail became old-fashioned in the age of plastic membership cards and ever-evolving reward ranges.

Sperry & Hutchinson also tried to reinvent themselves in 1989, launching a plastic member card which could be swiped at cash registers to earn points. This evolved into S&H Greenpoints in 1999, an attempt to weave the 104-year-old company into the dot-com boom. By 2000, they had attracted 88 participating retailers, including OfficeMax.com, Borders.com and LandsEnd.com.[41] In 2006, the company was purchased by Pay By Touch for over US$100 million in cash and stock.[42] Their demise should be listed alongside such companies as Kodak, such was the scale of their operation and influence on retail marketing globally, not to mention their penetration of households.

Increasing competition, combined with the birth of the digital age, led to a loyalty program innovation boom from the 1990s onwards. Coalition programs launched online reward stores with thousands of consumer products and gift cards, expanded into insurance products, branded credit cards, financial services, food and wine clubs, massive partner networks and digital marketing agencies. In addition, they developed specialised capabilities in data capture, usage, and monetisation, all of which will be explored in later chapters.

Tesco (1995)

Tesco opened their first permanent store in Burnt Oak in 1929. After expanding through the 1930s and listing on the London Stock Exchange in 1947, Tesco introduced self-service retailing in 1948 and opened its first supermarket in 1956, laying the groundwork for rapid post-war growth.

In response to rising loyalty stamps competition (including major competitor Fine Fare supermarkets which began offering Sperry & Hutchinson Pink Stamps in the early 1960s), Tesco adopted Green Shield Stamps in 1963, becoming one of their largest UK clients. The stamps program bolstered customer loyalty and helped Tesco compete with emerging discounters and evolving consumer expectations.

By 1977, Tesco recognised that the cost and complexity of managing a stamp-based loyalty program hindered its ability to offer everyday low prices. Under ‘Operation Checkout’, Tesco abandoned Green Shield Stamps, saving an estimated £20 million annually, and redirected those savings into nationwide price cuts. This strategic shift away from trading stamps marked a decisive turn toward direct price competition and operational efficiency. It also signalled the beginning of the end for Green Shield stamps, which suffered a slow demise that eventually led to termination of the program in 1991.

Eighteen years later, in February 1995, Tesco launched Clubcard, widely regarded as the first loyalty program to leverage data-driven marketing at true retail scale. Clubcard was the first grocery-industry loyalty program to capture detailed, item-level purchase data for every member via a magnetic-stripe card. That data was then analysed (with the support of start-up data analytics firm dunnhumby) to create personalised vouchers, targeted promotions, and category-specific campaigns.[43]

Clubcard managed to generate a 28 per cent increase in member spend within its first year and approximately £60 billion in incremental sales over its first decade.[44] While early airline frequent flyer programs collected basic transactional data, none matched Clubcard’s breadth of real-time retail data capture, sophisticated customer segmentation, and comprehensive use of analytics to shape product assortment, pricing, and marketing. This made it the pioneer of data-driven loyalty marketing at scale, kicking off a new era of loyalty program evolution that has since spread around the world and into many other industries.

Cryptocurrencies and Tokenised Assets (2017)

From 2017, several start-ups launched new coalition programs rewarding members with tradeable ‘cryptocurrencies’, such as Bitcoin, Ethereum and branded crypto tokens. The novel variation with cryptocurrencies as a loyalty currency was that the value could increase or decrease based on speculative trading behaviour. The approach taken by start-ups was to establish a coalition program to drive demand for the cryptocurrency, which would subsequently increase in value, benefiting existing members. Most programs failed to deliver the sustained demand necessary to protect the market price of their cryptocurrencies, which instead decreased in value aligning with market sentiment. Programs offering Bitcoin have achieved market traction and continue to build global engagement.

Other programs have evolved to reward members with ‘tokenised assets’. Examples include BrickX (reward members with real estate), Almonds AI (reward members with carbon offsets/tree planting), and Bits of Stock (reward members with partner company shares). Shares and real estate allow the member to earn dividends on their tokens (a hark back to co-operative programs). Carbon credits can be offset against tree plantings or even traded. Ostensibly any physical asset can be tokenised, opening up an exciting new future in the evolution of loyalty currencies.

*

From a loyalty program design perspective, the most fascinating aspect of the historical review is that the core design of a currency-based loyalty program has remained consistent throughout time. The currencies have changed constantly (tokens, trade marks, checks, tickets, coupons, certificates, stamps, miles, points, cryptocurrencies, tokenised assets, and more), but the fundamental program design has not changed. All the companies included in the historical research followed the exact same approach: providing a tokenised currency to a customer when they spent and allowing the customer to redeem the accumulated currency for a desirable reward.

Do loyalty programs work?

Do loyalty programs work? Review our case studies of brands that and generating incredible results from their loyalty programs.

References

[1] Kemp, B. J., 2005, Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization, 2nd Edition.

[2] Nagle, J., 1971, ’Trading Stamps: A Long History’, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/12/26/archives/trading-stamps-a-long-history-premiums-said-to-date-back-in-us-to.html. Accessed 22 April 2020.

[3] Fuld, G. & Fuld, M., 1975, U.S. Civil War Store Cards, Quarterman Publishing.

[4] Mudd, D., 2015, ‘Hard Times Tokens’, American Numismatic Association, https://www.money.org/ana-blog/TalesHardTimesTokens. Accessed 22 April 2020.

[5] Barnard, B. W., 1917, ‘The Use of Private Tokens for Money in the United States’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 600-634.

[6] Judd, A., 1999 ‘Why Did Consumer Co-operative Societies in Britain use Tokens?’ Journal of Co-operative Studies,Vol. 32, No. 1, pp.95-105.

[7] Welcome To Lennoxtown, https://www.welcometolennoxtown.co.uk/co-operative_society.htm. Accessed 7 September 2025.

[8] Trails and Tales, ‘LX-01 The Cooperative’, https://www.trailsandtales.org/trails/heritage/the-cooperative. Accessed 27 September 2025

[9] Judd, A., 1999 ‘Why Did Consumer Co-operative Societies in Britain use Tokens?’, Journal of Co-operative Studies Vol. 32, No. 1.

[10] Ingam, J.N., 1983, Biographical dictionary of American business leaders, Greenwood Press.

[11] National Commission on Food Marketing, 1966, ‘Organization and competition in food retailing’, Technical study No.7, p. 41.

[12] B. T. Babbitt, Incorporated, 1905, Mailing List of Premiums.

[13] B. T. Babbitt, Incorporated, 1912, B.T. Babbitt’s Profit Sharing List.

[14] Levinson, M., 2012, ‘Don’t Grieve for the Great A&P’, Harvard Business Review.

[15] The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co., 1890, 1890 Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. Coupon Premium – Handstamp of Big Bleecker.

[16] Levison, M., 2011, The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America, Hill & Wang.

[17] The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co., 1908 Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co Catalogue.

[18] Levison, M., 2011 The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America, Hill & Wang.

[19] Grand Union Tea Company, 1903, Catalogue of Premiums.

[20] Nagle, J., 1971, ’Trading Stamps: A Long History’, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/12/26/archives/trading-stamps-a-long-history-premiums-said-to-date-back-in-us-to.html. Accessed 22 April 2020.

[21] Hunsicker & Warmkessel, 1890, People’s Trading Coupon, Allentown, PA.

[22] Dahlsad, D., 2013, ‘Inherited Values’, http://www.inherited-values.com/2013/09/meet-me-down-by-schusters-vintage-department-store-memories-collectibles/. Accessed 4 May 2020.

[23] L.H. Parke & Co., 1900, Rhymes and chimes for dismal times. Displayed with permission from Hagley Museum and Library, who the authors thank for their generosity

[24] Lonto, J. R., 2013, ‘The Trading Stamp Story,’ StudioZ-7 Publishing, http://www.studioz7.com/stamps.html. Accessed 4 May 2020.

[25] Sperry & Hutchinson Company, 1966, Ideabook of Distinguished Merchandise: 70th Anniversary Edition, S&H Green Stamps.

[26] National Commission on Food Marketing, 1966, ‘Organization and competition in food retailing’, Technical study No.7.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] United Cigar Stores, IMASCO, http://www.imascoltd.com/united-cigar-stores/. Accessed 7 April 2020.

[31] United Cigar Stores Company of America, 1924, ‘Premium Catalog’.

[32] Betty Crocker, 2017, ‘The story of Betty Crocker’, https://www.bettycrocker.com/menus-holidays-parties/mhplibrary/parties-and-get-togethers/vintage-betty/the-story-of-betty-crocker Accessed 2 May 2020.

[33] McKinney, M., 2006, ‘Betty Crocker closing the book on its catalog sales’, Minneapolis Star Tribune, https://www.chron.com/life/article/Betty-Crocker-closing-the-book-on-its-catalog-1506961.php. Accessed 2 May 2020.

[34] Betty Crocker, 1968, Betty Crocker Coupon Catalog, No 6.

[35] Wilcoxen, W., 2006, ‘Betty Crocker retires her catalog’, MPR News, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2006/11/28/bettycrocker. Accessed 2 May 2020.

[36] Mason, T., 2019, Omnichannel Retail, Kogan Page.

[37] Everett, M. R., 1995, Diffusion of Innovations, 4th Edition, The Free Press..

[38] De Boer, E. R., 2018, Strategy in Airline Loyalty: Frequent Flyer Programs, Palgrave Macmillan.

[39] McKinney, M., 2006, ‘Betty Crocker closing the book on its catalog sales,’ Minneapolis Star Tribune, https://www.chron.com/life/article/Betty-Crocker-closing-the-book-on-its-catalog-1506961.php. Accessed 2 May 2020.

[40] Wilcoxen, W., 2006, Betty Crocker retires her catalog, MPR News, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2006/11/28/bettycrocker. Accessed 2 May 2020.

[41] Slatalla, M., 2000, ‘Clicks, Not Licks, as Green Stamps Go Digital’, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2000/03/09/technology/online-shopper-clicks-not-licks-as-green-stamps-go-digital.html. Accessed 1 May 2020.

[42] The Wise Marketer, 2006, ‘Pay By Touch snaps up S&H Solutions & Greenpoints’, https://thewisemarketer.com/headlines/pay-by-touch-snaps-up-sh-solutions-greenpoints-2/. Accessed 2 June 2020.

[43] Humby, C., Hunt, T., & Phillips, T., 2008, Scoring Points: How Tesco Continues to Win Customer Loyalty.

[44] Davis, G., 2025, ‘Clubcard at 30 – the evolution of retail loyalty,’ Computerweekly.com, https://www.computerweekly.com/feature/Clubcard-at-30-the-evolution-of-retail-loyalty. Accessed 7 September 2025

[1] Rowell, D. M., 2010. “A History of US Airline Deregulation Part 4 : 1979 – 2010 : The Effects of Deregulation – Lower Fares, More Travel, Frequent Flier Programs”. The Travel Insider. Accessed 26 October 2025.

[2] Arnt, G., ‘Frequent Flyer programs’, Everything Everywhere podcast, episode 1865. Accessed 26 October 2025.

[3] Everett, M. R., 1995, Diffusion of Innovations, 4th Edition, The Free Press..

[4] De Boer, E. R., 2018, Strategy in Airline Loyalty: Frequent Flyer Programs, Palgrave Macmillan.

*All images of loyalty history memorabilia are from the author, Philip Shelper (unless stated).